Grave of the Fireflies (火垂るの墓, Hotaru no Haka) is a feature-length animated film written and directed by Isao Takahata, produced by Studio Ghibli in association with Shinchosha Publishing and distributed by Toho. It premiered in Japan on April 16, 1988, and was billed as a double-feature with My Neighbor Totoro. The film stars Tsutomu Tatsumi, Ayano Shiraishi, Yoshiko Shinohara and Akemi Yamaguchi.

Based on the semi-autobiographical novel of the same name by Akiyuki Nosaka, which was first serialized in the October 1967 issue of All Tribute (オール讀物). Set in the city of Kobe and Nishinomiya, Hyōgo Prefecture, the film tells the story of two siblings, Seita and Setsuko Yokokawa, and their desperate struggle to survive during the final months of the Second World War. This is the first film produced by Shinchosha Publishing, who hired Studio Ghibli to do the animation production work.[1]

Some critics, most notably Roger Ebert, consider it to be one of the most powerful anti-war movies ever made.[2] Animation historian Ernest Rister compares the film to Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List and says, "it is the most profoundly human animated film I've ever seen."

Besides this film, the original novel was adapted several times into manga, television dramas, live-action movies and a chorus suite in Japan. The film helped popularize the candy Sakuma Drops.

The film is available for streaming on Max, and purchasable on most digital storefronts.

Poster's Catchphrases[]

- "I decided to live at the age of 4 and 14." (4歳と14歳で、生きようと思った)

- "I came to deliver what I forgot." (忘れものを、届けにきました)

Plot[]

The Burnt-out Area[]

"September 21, 1945. That was the night I died."

Seita's spirit watches over his dying self in the train platform. He is soon reunited with his sister Setsuko.

The movie begins in modern-day Sannomiya Station, Kōbe, Hyōgo Prefecture, but then quickly flashes back to the past. Seita lies on the platform in rags and is dying from starvation. An onlooker remarks at how dirty he looked while another says, "The American troops will be arriving soon. It would be an embarrassment if they find such a guy here at the station."

Later that night, a janitor comes and digs through his things; finding a candy tin that contains Setsuko's ashes. He throws it out, and from there springs the spirits of Setsuko, Seita and a group of fireflies. The implication is that their spirits now haunt the station and that they will now provide the narrative throughout the story.

Mother's Death[]

"No need to worry. We should be safe here."

"Where did Mommy go?"

"She's at the air-raid shelter. The shelter behind the fire station. She said it could withstand the direct hit of a 250 kilo bomb. There's no need to worry. Mom's probably at the Nihon Matsu Station. We arranged to meet there. Let's go there after we rest a while."

"Are you all right?"

"I lost my sandal."

Seita and Setsuko flee the fire bombings in their hometown, an attack that led to the death of their mother.

As Seita begins to recount his past trauma, things flash back to the end of World War II, during the Kōbe fire bombings by American B-29 bombers. Setsuko and Seita, the two siblings and protagonists, are left to secure their house and their belongings in order to allow their mother, who suffers from a heart condition, to precede them to the bomb shelter.

The young boy carries Setsuko on his back, and runs through the streets where people jostle each other in panic; he finally flees towards the sea. Once in safety, and after having let pass the black rain of the bombs that pours on his town, he undertakes to return towards the charred ruins with his little sister. A man announces through a megaphone the gathering at school for the inhabitants of his neighborhood.

Learning that his mother has been injured, he leaves Setsuko with a family friend and goes in search of his mother. Their mother had been fatally injured in the air raid and is taken to a makeshift hospital which is actually a school, where she dies from burn wounds. Setsuko cries bitterly, while Seita tries to entertain her, hiding his own distress. She is cremated with several other corpses, and Seita collects a few meager bones in a small box.

Early Summer[]

"I don't like zosui."

"The pickled plums that I brought... There're no more?"

"That thing... You know that it ran out a long time ago."

"Look. Lunch will be white rice, so bear it and eat it."

"Cut it out! For those that are here during the day, lunch will also be zosui! Why should the lunch for those that work for the country and those that just sit around all day be the same? Seita-san. You're old enough; start thinking about how you can be of help. You two don't give us any rice but expect to eat it. It just doesn't go that way. No way."

When Seita and Setsuko moved in with their aunt, they immediately shirked their responsibilities.

Having nowhere else to live, Setsuko and Seita go to live with their aunt at Nishinomiya, and write letters to their father. On the second day that they stay there, Seita goes out to get the left over supplies which he had buried in the ground to preserve them before the bombing which killed their mother. He gives all of it to his aunt, but hides a small tin of fruit drops.

The cohabitation goes smoothly for several days: the widow takes advantage of the provisions, while Seita and Setsuko receive a roof on their head and food. But soon the situation deteriorates. The aunt begins to reproach Seita: he does nothing to help at the household, demands too much to eat and his sister cries at night, preventing those who work from sleeping. Seita thinks the situation is temporary and hopes to hear from her father, a naval officer soon. In order to pass the time, he takes Setsuko to the seaside and plays with her carefree, which reminds the young boy of the happiness of the past.

Under the Cherry Blossoms[]

"I'm hungry. I'm thirsty."

"All right. Lick these drops. Mom had seven thousand yen saved in the bank. Seven thousand yen! If there's that much, we can manage plenty. There's no need to worry anymore."

"You guys are lucky. In times like these, no matter how much money you offer, you can't buy these items. Nowadays, there're no items to sell and the business is dry. Especially metal products. Can't find them anywhere."

Frustrated in their aunt's nagging, Seita and his sister foolishly moved out to a remote shelter.

The atmosphere at home had become tense. One evening, she asks Seita to sell her mother's things to bring back some rice. Setsuko, who remembers her mother's kimonos, is shaken with heavy sobs. Seita then discovers that his mother had provided them with a comfortable sum, allowing them to feed themselves without depending on their aunt. During a nighttime air raid alert, Seita spots an abandoned refuge that could become their new home, far from their aunt's nagging.

This prompts Seita and Setsuko to move out and live in that old, abandoned bomb shelter. Setsuko is delighted, imagining the shelter as that of a real home. The two children thus continue their existence without worrying about the future.

Grave of the Fireflies[]

And... we've traded all of Mom's kimono for rice and don't have anymore. From your place, we've purchased many things with money before..." "I'm not talking about kimono or money. Though we're a farm, we don't make enough to distribute it to others all the time. Never mind that; don't you have other relatives?"

"Well... I can't get in touch with them."

"Then, it's better for you to go back to that house. Besides, everything's rationed now. If you're not part of a community group, you can't eat. Apologize and ask them to let you stay."

"Sorry to have bothered you. I'll try another place."

Seita relocates to an abandoned shelter, thinking their leftover money would be enough to survive through the war.

In the evening, the two children collect a good quantity of fireflies which they release in the cabin. The light of the fireflies reminds Seita of fireworks, during the naval review after which her father went to war. And the lights to become DCA tracer bullets, destroying enemy bombers.

The next day, Seita finds her sister digging a hole in the ground. Puzzled, he asks her the reason for this behavior. Innocently, Setsuko replies that she is digging a grave for the fireflies, her aunt having explained to her that this had been done for her mother. Overwhelmed by this gesture, remembering the unbearable images of her mother's body thrown into a pit, Seita can no longer contain himself and cries bitterly. He promises Setsuko that they will one day visit their mother's grave.

Sunset Colors[]

Setsuko slowly succumbs to malnutrition.

Gradually, they begin to run out of rice, and Setsuko begins to starve. Seita turns to stealing from local farmers and looting homes during air raids for supplies. When finally caught, he realizes his desperation and takes an increasingly-ill Setsuko to a doctor, who informs him that Setsuko is suffering from malnutrition. When he learns of his father's death, Seita removes all the money from their mother's bank account and purchases a large quantity of food.

Song of Sorrow[]

"Setsuko, I'm sorry I'm late. I'll cook you a white rice porridge."

"It went down... It went up... Ah, it stopped..."

"Luckily, I was able to buy fish and eggs. And... Setsuko! What are you licking! These are marble pieces. It's not drops! Today, I've gotten something much better... It's something you like."

"Here you go, Nii-chan..."

"What's this, Setsuko?"

"It's a meal. I'll give you the the cooked okara..."

Rushing back to the shelter, he finds a dying Setsuko hallucinating. She is sucking marbles which she believes are fruit drops. She offers him 'rice balls' which are really only made out of mud. Seita hurries to cook, but it's too late: Setsuko dies of starvation.

Seita and Setsuko's spirit stare at modern day Japan.

After watching over his sister's lifeless body, Seita decides to cremate his little sister himself. He uses supplies donated to him by a farmer and places Setsuko in a large wicker basket and sets it on fire, while the fireflies fly around to the sky. He then leaves her ashes in the fruit tin, which he carries with his father's photograph, until his own death from malnutrition in Sannomiya Station a few weeks later.

It is now present day. Setsuko runs up towards Seita. Both ended up in death. With her head on her brother's lap, she falls asleep peacefully, as a few fireflies fly through the air. Seita looks at the viewer with a depressed look, then turns his head towards the lights of the skyscrapers of a modern city.

Characters[]

- Seita

- A 14-year-old boy, Seita is orphaned following the deadly bombings of the city of Kobe. Living with his aunt with his sister, he quickly understands that in these times of war and famine, he can only count on himself to provide for his sister. He therefore decides to live alone with her in an abandoned shelter, refusing any participation in the war effort or in collective life. But the young boy does not manage to assume his new responsibilities, and becomes the helpless spectator of his sister's slow agony. We do not know the journey Seita had to undergo between the death of his sister and his own agony. But his tragic fate is mitigated by the fact that her "ghost" joins that of his little sister, as in the past.

- Setsuko

- Sister to Seita, Setsuko is a lively 4-year-old girl. While one might think she is carefree, she nevertheless understands more things than she seems. She thus knows that her mother is dead, despite all Seita's precautions. But she's still a little girl of her age nonetheless, crying in front of her empty candy box or bowl of tasteless porridge. However, it turns out to be too fragile and too young to resist malnutrition. She gradually sinks into illness and passes away peacefully after thanking her brother.

- Seita's aunt

- Sister of Setsuko and Seita's father, the aunt has to take in the two children following the death of their mother. She also shelters her daughter and a man working for the war effort. Exasperated by the inertia and recklessness of Seita and Setsuko while the war rages on, she quickly seeks to appropriate the resources brought by the orphans, considering this acquisition as normal in the face of such interference. In the end, her behavior will cause the two children to flee her house and her constant reproaches.

- Farmer

- An angry farmer who abuses Seita for stealing some of his crops. An officer threatens to charge him with assault.

Story Origins[]

Author[]

Nosaka Akiyuki was seen as a very colorful personality in Japan. His guilt over his sister's death drove him to write Grave of the Fireflies.

Nosaka Akiyuki was born in Kamakura, a seaside Japanese city just south of Tokyo in 1930, but his mother died soon after giving birth and Nosaka was adopted by an aunt in Manchidani-cho, Kobe (far to the west), whom he believed to be his mother. Nosaka's father did not maintain contact, and remarried.

When the war came to Japan, Nosaka, too old to be evacuated and too young to be conscripted, became part of the cohort charged with air-raid defense. When Kobe was fire-bombed in June 5, 1945, his adopted father was killed and his "mother" badly injured. Nosaka ran away with Keiko, his infant "sister", but – unlike in the anime – he, and the adults around him, failed to care adequately for her, and she died in August 1945.

He subsequently moved to Tokyo, where he was caught stealing and was left in a juvenile detention center, where he witnessed many of his fellow inmates die of starvation. Finally, his natural father – by now a local councilor – was contacted, and reclaimed him.

Interpretation[]

"The main character is rather spoiled for a wartime child. In that sense, I think today’s children would become just like him if they were put into the same situation. That brother and sister can only survive that harsh environment by locking themselves up into a world of their own. When they lose their sole guardian, their mother, the older brother decides to become the guardian of his little sister, even if it means making an enemy out of the entire world.

He gets to the point where he thinks he wouldn’t mind turning himself into nourishment for his sister. On the one, that’s very tragic, but it’s also a blessed situation. For Seita, it’s like he can try to build a heaven for just the two of them.

After all, it’s a double-suicide story."

Various editions of Nosaka Akiyuki's novel of Grave of the Fireflies.

The story is based on the semi-autobiographic novel by the same name, whose author, the late Akiyuki Nosaka, lost his sister Keiko due to malnutrition in 1945 wartime Japan. He blamed himself for her death and wrote the story so as to make amends to her and help him accept the tragedy. Nosaka has described his path as circling incessantly around a vortex – and literary critic Setsuji Shimizu has likened this circling to that of a vulture circling his own memory.[4] When describing Keiko in his novel,

"I couldn't take the place of my mother and father for the death of my one-year-and-four-month-old sister, and (the novel) was the least I could do for my sister, who had nothing more than fireflies in her mosquito net to distract her... In middle of the night, against the night wind, I would wash the lice from my sister's skin with bottled water taken from the sea... I wish I had at least petted my sister as much as Seita did in the novel... I wasn't that kind."[5]

Seita's death in the opening is seen by the author as a suicide, and his journey in the film his personal "Hell" until he reaches "Heaven".

In an interview, Akiyuki Nosaka recounted that right after he collected his sister's bones and started wandering aimlessly, electricity was restored to the city. The lights suddenly swept through the darkness. After struggling in Hell, he suddenly finds himself in Heaven. At the end of the film, Seita and Nosaka have reached the end of a long and painful experience.

In another interview on Animage in 1987, Director Isao Takahata likened the book to a "double-suicide" play,

"I feel that very strongly when I first read the book. I felt something in common with Chikamatsu’s double-suicide plays. I thought it was that in its structure, as well. It starts with the premise that the main characters must die, and the story follows the path to their death. Except that I think you were right when you said “Heaven”. I’d like to depict it that way in the movie, too."

Mamoru Oshii weighed in on the story saying, “It's an immoral world as it is a story of incest. And the image of death is lined up just behind it. In that sense, it's an erotic film and it gave me a cold sweat."[6]

Adaptation[]

"Setsuko becomes affected by the change in the environment and the change in her brother, and has to grow up quickly. Eventually, she assumes the role of his mother at times, and at other times, the role of his lover. She is overwhelmingly dependent on him, but she also becomes his spiritual support. So when the sister starts to perish physically, the brother has no choice but see her becoming even more beautiful. It’s like the sweet delusions of boyhood. In the end, it turns out that the days leading up to their deaths are like the development of a love story."

"Those were very oppressive times, when 'totalitarianism,' the worst kind of social life, was considered to be righteous. Seita tries to resist such totalitarianism and build a 'pure family' with Setsuko alone, but is such a thing possible or not? But can we criticize it? The reason we modern people can easily sympathize with Seita emotionally is because the times have reversed. If the times are reversed again, I have a horrible feeling that there will come a time when there will be more opinions denouncing Seita than his relative's aunt."

-Isano Takahata

Takahata explains that although the siblings succeed in establishing a closed family life, their refusal to live in harmony with those around them and their failure to make it in society is something that can be seen in the lives of people today.

野坂昭如 『火垂るの墓』のアニメーションについて

Grave of the Fireflies author Nosaka Akiyuki on how he feels about Takahata adapting his experience some 43-years prior in animated form.

Having lived the horror of the end of the Second World War in Japan, when he was only 14 years old, Nosaka is deeply marked by the American bombings. His adoptive mother dies under the bombs, her sister dies of hunger, and Nosaka is convinced of her guilt in these two dramas. He finds himself locked in a reformatory after food thefts. Saved by his biological father at a juvenile detention center, Nosaka nevertheless retained an oppressive feeling of guilt in him. When he wrote the short story The Grave of the Fireflies twenty years later, the autobiographical link seems obvious. However, Nosaka chose to sacrifice Seita. We can see in this act of writing the way to regain dignity, to exorcise the demon that haunts him: Seita does not survive his family and therefore does not have to suffer the feeling of having betrayed his fate by surviving to his.

Director Isao Takahata tasked Studio Ghibli colorist Michiyo Yasuda to work with dark color tones, something she admitted hadn't been done often in their previous projects.

Isao Takahata respected this interpretation very scrupulously. Indeed, only the passages where Seita and his sister contemplate their past life as spirits has been freely adapted by Takahata. The glowing hue of the introduction, contrasting with the dominant cold tones in the rest of the film, will punctuate the story thereafter. The occasional shift of these dreamlike sequences in relation to the general realistic subject allows, in a very sober, uncluttered way, a certain dramatization of the story.

According to French fansite Buta Connection, in the short story, the identity of the narrator is unclear, but one can assume that it is the voice of the author. This narrator tells the story from a third person perspective, creating some distance. In the film, Seita's mind is free to move, and as the narrator, speaks from a first person perspective. He becomes a witness, whose fate we know from the start ("September 21, 1945, I died"). This stylistic process allows the viewer to identify with the characters and therefore gives an intense and dramatic tone to the film. As to Takahata's reasons for adapting such a tragic story into the animated medium, he explains,

"It’s natural that many animated stories are adventure ones, and that’s not a bad thing in itself. But at the same time, I’ve felt a contradiction in that, whether it’s animated or not, a wartime story tends to be moving and tear-inducing, but the young people reading or watching such story have a certain inferiority complex in relation to it. They think people back then were much more noble and that they wouldn’t be able to do such things themselves. But I think that’s not right. We make stories to give courage to the people, but then the audience feels the story has nothing to do with them. So I wanted a common ground for the audience to relate to. I felt that way before I came in contact with this book."

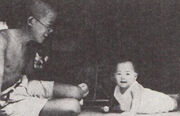

A photo of Akiyuki Nosaka with his younger sister Keiko in year 1945. Nosaka disparages himself as a liar after publishing Grave of the Fireflies. Photo courtesy of Yoko Nosaka.[7]

In the film, we also learn the nature of the two children's ailments: it is scabies (skin infestation caused by mites). Finally, the box of candies whose existence Nosaka evokes in the first lines of his short story takes up much more space in the film The Grave of the Fireflies. The contents of this box provide these two orphans with one of the rare moments of happiness, even reprieve. It will also be the receptacle for Setsuko's ashes, a derisory urn, like the story of these two orphans whose existence is thrown to the ground.

The film is also less raw than the book, which is intended to be a very raw approach to the reality of war. This is characteristic of Nosaka's style, known for his provocations, his cynicism and his taste for the description of scatological phenomena. In the book, this literary inclination does not shock, the author describes the horror of war, famine and malnutrition, which therefore involves terrible crises of dysentery, diarrhea. Takahata preferred to avoid representing this too harsh aspect in his film, the weight of the images would probably have shocked a large number of viewers and distracted attention from the essential, the fate of Seita and Setsuko.

Takahata's film nevertheless remains very faithful to Nosaka's work. It suffices to compare a few lines to the images to understand the formidable work of adaptation of Takahata, who knew how to draw all the quintessence of words in images.[8]

About the Title[]

Japanese nouns do not change to form plurals, so hotaru can refer to one firefly or many. Seita and Setsuko catch fireflies and use them to illuminate the bomb shelter in which they live. The next day, Setsuko digs a grave for all of the dead insects, and asks "Why do fireflies die so soon?", so the title might serve to heighten the symbolic and thematic significance of the incident.

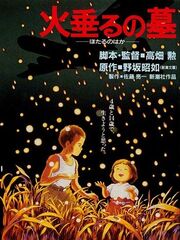

Poster of the Grave of the Fireflies, where the aforementioned fireflies symbolize many things in Japanese culture.

Alternatively, it may be that Setsuko is the "firefly" of the title, herself dying young. If so, the title can be interpreted as A Grave for a Firefly. Or to maintain the lack of distinction over plurals, The Firefly Grave could also be used.

In the Japanese title of the movie the word hotaru (firefly) is written not with its usual kanji 蛍 but with the two kanji 火 (hi, fire) and 垂 (tareru, to dangle down, as a droplet of water about to fall from a leaf). This can evoke images of fireflies as droplets of fire. Some consider that this evokes senkō hanabi, a fire droplet firework (a sparkler firework which is held upside down). This is particularly poignant in this respect because it must be held very still or the fire will drop and die, which represents the fragility of life. Senkō hanabi also evoke images of family, because it is a summer tradition in Japan for families to enjoy fireworks together. Fireworks, in general, are considered to be another symbol of the ephemerality of life. Watching fireflies is another summer family tradition. Together, the references evoke the bond between Seita and Setsuko, but at the same time emphasize their isolation due to the absence of their parents.

Alternatively, pairing the two kanji for "fire" and "dangle down" may also be a metaphor for the experience of aerial bombing using incendiary weapons. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the Japanese during the war sometimes referred to falling and exploding incendiary bomblets as "fireflies."

Firefly Symbolism[]

水野晴郎 解説「火垂るの墓」

Well-known movie commentator Haruo Mizuno provides commentary for Grave of the Fireflies.

Particular firefly symbolism in the movie:

- Actual fireflies (who died and are buried by Setsuko)

- The children themselves, especially Setsuko, who died young

- Kamikaze planes and pilots: Setsuko observes that a passing kamikaze plane looks like a firefly

- Incendiary bomblets (as in the title kanji)

Mature fireflies which emit light have extremely short life spans of two to three weeks and are traditionally regarded as a symbol of impermanence, which resonates with much of classical Japanese tradition (as with cherry blossoms). Fireflies are also symbolic of the human soul ("Hitodama"), which is depicted as a floating, flickering fireball. Heikebotaru (平家蛍, Luciola lateralis), a species of firefly that exist in the Western region of Japan, is so-called because people considered their lights, hovering near rivers and lakes, to be the souls of the Heike family, all of whose members perished in a famous historic naval engagement - the Battle of Dan-no-ura.)

Ending Interpretation[]

During a lecture held at Royal Abbey of Fontevraud on July 2 to 6, 2007, Takahata explained in a lecture why the film ended in contemporary Japan,

"There is one thing I would like to explain to you first. In Japan, Buddhism is an important religion (I myself am a Buddhist), but it is about a Buddhism which underwent a certain number of changes compared to its starting doctrine which came from India or China. He mingled with an ancestor worship which is still very strong today in Japan. To give you some explanatory elements, it is about a set of beliefs which wants that the deceased did not really leave but are in a place far from our and inaccessible, while remaining very close to us. And they see us. It can be seen as luck, but it can also be a form of surveillance. Whatever we do, those who are dear to us see us. And it is rather this aspect that I wish to express in this final.

But in a sense, you are also right, because in the city of Hiroshima, where the first atomic bomb fell, there is a monument to the dead which has an engraved mention which says: "Rest in peace because we will not remake them. same mistakes." This is a translation which poses some problems for the Japanese has no subject. Rather, it could be literally translated as: "Mistakes (or mistakes) will not be repeated."

"I think that in this absence of subject that the Japanese language allows, and which makes this inscription special, is precisely linked to this belief that the dead are always present. In any case, it is also the starting point for a certain number of controversies, since in the absence of a subject one can also wonder who made the mistake and which? And in the state, this mention does not allow to decide."

Behind the Scenes[]

Development[]

The Grave of the Fireflies was Isao Takahata's first film produced under Studio Ghibli. Wanting to return to directing after producing Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Castle in the Sky, Takahata embarked on a live-action film retracing the history of the Yanagawa Canal. Using the proceeds from Nausicaä, The Story of Yanagawa's Canals was produced by Hayao Miyazaki and completed in 1987. It was at this time thatTakahata had begun submitting several other film proposals to Tokuma Shoten, the parent company of Studio Ghibli, including an adaptation of Akiyuki Nosaka's short story, The Grave of the Fireflies.

Miyazaki, meanwhile, had begun development of My Neighbor Totoro. Chairman Yasoyoshi Tokuma was initially reluctant to produce Takahata's film, but was convinced by Toshio Suzuki. Suzuki had an original idea: to combine the productions of The Grave of the Fireflies and My Neighbor Totoro. Indeed, a historical drama would have an educational purpose and would attract many school classes, ensuring a minimum number of entries. But to produce two films at the same time, one of the two films must be financed by another producer. He then contacted the famous publisher Shinchôsha, who at the time had a great interest in film adaptations of his books, and offered the publishing house to adapt The Grave of the Fireflies.

Suzuki explains to Shinchôsha that Tokuma was going to produce a new Miyazaki film and that, if the publisher agrees to fund The Grave of the Fireflies , it was quite possible to release both projects at the same time at Studio Ghibli. As Shinchôsha is a much older and more established than Tokuma Shoten, the decision to proceed with Miyazaki's project is taken very quickly.

Production[]

Takahata said that he had considered using non-traditional animation methods, but because "the schedule was planned and the movie's release date set, and the staff assembled, it was apparent there was no room for such a trial-and-error approach." He further remarked that he had difficulty animating the scenery since, in Japanese animation, one is "not allowed" to depict Japan in a realistic manner. Animators often traveled to foreign countries to do research on how to depict them, but such research had not been done before for a Japanese setting.

"I worked on a anime called Heidi of the Alps before, and the main character starts out at the age of five. I thought I could just depict the idealized 5-year old girl from the book, but I’ve never handled a girl younger than that. On top of that, I haven’t depicted Japan before. That’s because, in Japanese animation, you’re not allowed to depict Japan with much realism. We can research a lot about foreign countries, though. If it’s Heidi, we can go to Switzerland to do research. But that hasn’t been done for a Japanese story."

Indeed, in the beginning, he had thought of this film from another perspective than the usual cellulo rendering: "It seemed to me that for this story, he was almost trying to find other means of animation than the only traditional cellulo, and that it was necessary to find the time to make tests to obtain another visual result, even if it means suffering from failures. " That's what he can do eleven years later, thanks to computers, with My Neighbors the Yamada .

However, when it came to work on The Grave of the Fireflies in 1987, Takahata was made to understand that it was not possible to experiment with anything, as the film was due for release in March of the year. Takahata was deadlocked, and it was then that Hayao Miyazaki came to say to him: "If you do not make this film today, there will undoubtedly be no other occasion, for you, to make a such movie. " Takahata was well aware and, willy-nilly, he decided to change direction and brings the film to a vision more suited to celluloid.

Anime Mook Grave of the Fireflies Storyboard Collection.

Takahata is customary for being late for his films. For The Grave of the Fireflies, he is no exception to the rule: the film is considerably behind schedule. The publisher Shinchôsha, producer of the film, however, forced Takahata to meet his deadlines. This will ultimately result in the film being released with an unfinished scene.

In addition to the shortness of the production period, there were technical problems due to the launch of two simultaneous productions. The workforce was absolutely not sufficient and the studio once again called on Tôru Hara (former Tôei, president of the Topcraft), for his long experience in management and production. Hara was therefore the producer on both films.

There was a lack of designers and Takahata absolutely wanted to work with Yoshifumi Kondô. At the time, the latter was working for Nippon Animation. But a talented designer was needed at the center of The Grave of the Fireflies team since Takahata did not draw. Hara understood this very well: he went to see Kondô and convinced him to come and work for them.

Detailed color instructions are given as cel painting was often outsourced to different studios.

This visit was decisive for the making of the film. Kondô indeed played a central role in the graphic genesis of the film, both in the creation and design of the characters and in the animation. He managed to restore the facial expressions as believable and moving as possible. One can only remain speechless in front of the realism of the gestures of the characters or the expressions of the girl. It is said that for Setsuko's gestures, he was inspired by those of Brigitte Fossey in Forbidden Games (1952). "In Forbidden Games, of course, there is of course the character of the girl played by Brigitte Fossey, quite remarkable and which certainly marked me. But I remember that when I saw this film for the first time, the character of the young boy, played by Georges Poujouly, marked me almost even more. He is a character who made a very strong impression on me when I discovered this film a very long time ago."[9]

Isao Takahata stuck very closely to the original novel, while adding significance to certain elements for narrative purposes.

For the sets, while for My Neighbor Totoro Miyazaki called on Kazuo Oga , Takahata worked with Nizô Yamamoto. One will notice the big difference between the works of the two artistic directors: the closed world of The Grave of the Fireflies is opposed to the very open world described in Totoro . The meticulousness with which the daily living environment is described in great detail, is based on a work of a quality which was undoubtedly the first foundation of the reputation of Studio Ghibli in their representations of the world.

Most of the illustration outlines in the film are in brown, instead of the customary black. Black outlines were only used when it was absolutely necessary. Color coordinator Michiyo Yasuda said this was done to give the film a softer feel. Yasuda said that this technique had never been used in an anime before The Grave of the Fireflies, "and it was done on a challenge." Yasuda explained that brown is more difficult to use than black because it does not contrast as well as black.

Dubbing[]

Appropriately aged children were cast in the roles of Seita and Setsuko, however at first, producers felt the five-year-old girl portraying Setsuko was too young. Due to her age, instead of completing the animation first and recording her voice to run parallel with the animation as with other characters in the film, they recorded her dialogue first and completed the animation afterward; the process was explained by Takahata in a 2002 interview.

Music[]

The film score was composed by Michio Mamiya. Mamiya is also a music specialist in baroque and classical music. The song Home Sweet Home was performed by coloratura soprano Amelita Galli-Curci.

Releases[]

→ See also Grave of the Fireflies/Release

| Country | Release Date | Format | Publisher |

|---|---|---|---|

| Japan |

April 16, 1988 | Theater | Toho |

| USA |

Autumn 1990 | VHS | N/A |

| USA |

July 26, 1991 | Theater | N/A |

| USA |

January 1993 | Theater | N/A |

| Japan |

January 2000 | VHS Re-Issue | N/A |

| USA |

January 25, 2006 | DVD | N/A |

Grave of the Fireflies and My Neighbor Totoro were released as a double feature in 1988.

The film was released on April 16, 1988, over twenty years from the publication of the short story.[10] The initial Japanese theatrical release was accompanied by Hayao Miyazaki's My Neighbor Totoro as a double feature. While the two films were marketed toward children and their parents, the starkly tragic nature of Grave of the Fireflies turned away many audiences. However, Totoro merchandise, particularly the stuffed animals of Totoro and Catbus, sold extremely well after the film and made overall profits for the company to the extent that it stabilized subsequent productions of Studio Ghibli.

Grave of the Fireflies is the only theatrical Studio Ghibli feature film prior to From Up on Poppy Hill to which Disney never had North American distribution rights, since it was not produced by Ghibli for parent company Tokuma Shoten but for Shinchosha, the publisher of the original short story (although Disney has the Japanese distribution rights themselves, thus replacing both the film's original Japanese theatrical distributor, Toho and original Japanese home video distributor, Bandai Visual).[11] It was one of the last Studio Ghibli films to get an English-language premiere by GKIDS.[12]

Home Media[]

The Grave of the Fireflies was released in Japan on VHS by Buena Vista Home Entertainment under the Ghibli ga Ippai Collection on August 7, 1998. On July 29, 2005, a DVD release was distributed through Warner Home Video. Walt Disney Studios Japan released the complete collector's edition DVD on 6 August 2008. WDSJ released the film on Blu-ray twice on July 18, 2012: one as a single release, and one in a two-film set with My Neighbor Totoro (even though Disney never currently owns the North American but Japanese rights as mentioned).

Various Grave of the Fireflies home releases for VHS.

It was released on VHS in North America by Central Park Media in a subtitled form on June 2, 1993.[13] They later released the film with an English dub on VHS on 1 September 1998 (the day Disney released Kiki's Delivery Service) and an all-Regions DVD (which also included the original Japanese with English subtitles) on 7 October 1998. It was later released on a two-disc DVD set (which once again included both the English dub and the original Japanese with English subtitles as well as the film's storyboards with the second disc containing a retrospective on the author of the original book, an interview with the director, and an interview with critic Roger Ebert, who felt the film was one of the greatest of all time.) on October 8, 2002. It was released by Central Park Media one last time on December 7, 2004.

Following the May 2009 bankruptcy and liquidation of Central Park Media, ADV Films acquired the rights and re-released it on DVD on July 7, 2009.[14] Following the September 1, 2009 shutdown and re-branding of ADV, their successor, Sentai Filmworks, rescued the film and released a remastered DVD on March 6, 2012, and plans on releasing the film on digital outlets. A Blu-ray edition was released on November 20, 2012, featuring an all-new English dub produced by Seraphim Digital.[15]

StudioCanal released a Blu-ray in the United Kingdom on July 1, 2013, followed by Kiki's Delivery Service on the same format.[16] Madman Entertainment released the film in Australia and New Zealand.

Accolades[]

- Blue Ribbon Awards (1991)

- Special Awards

- Chicago International Children's Film Festival (1994)

- Animated Feature Film

- Rights of the Child Award

Differences from Original[]

The story is almost the same as the original, but there are some differences. Seita's death was drawn at the beginning, starting with the ghostly narration of Seita's "I'm dead" and cutting back, and the composition of the original from the Kobe air raid to the station yard where Seita is dead. It traces almost faithfully, but the production of the latter half, especially the depiction of the scene of Setsuko's death (in the original, Seita died while swimming in the pond), and at the beginning from the modern Sannomiya station to the past Sannomiya station is such configuration that leads to Kobe city silhouette of modern times switched places and the last in an anime original, it and this that Seita, which became a ghost is seen repeatedly to the present day a few months until they will die suicide products are Is carefully calculated and drawn so that you can see it only at the beginning.

When the screen turns red during the work, it means that the ghosts of Seita and Setsuko have appeared and are looking closely, staring at the memory over and over again, and it is directed red like Ashura. However, in the anime picture book, this part is largely omitted, and there is only a scene that suggests that the two people who are looking at the modern city of Kobe at the end are ghosts in a red state. Anime picture books generally faithfully follow the main part of the movie, but explain the lines, actions, and scenes that suddenly appeared.

Voice Cast[]

| Character | Original | 1998 Version | 2012 Version |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seita Yokokawa | Tsutomu Tatsumi | J. Robert Spencer | Adam Gibbs |

| Setsuko Yokokawa | Ayano Shiraishi | Rhoda Chrosite | Emily Neves |

| Mrs. Yokokawa | Yoshiko Shinohara | Veronica Taylor | Shelley Calene-Black |

| Seita's aunt | Akemi Yamaguchi | Amy Jones | Marcy Bannor |

| Yokokawa cousin | Kazumi Nozaki | Shannon Conley | Susan Koozin |

| Doctor | Michio Denpō | Crispin Freeman | David Matranga |

| Obayashi Chairman | Kōzō Hashida | George Leaver | Samuel Roman |

| Woman who takes care of Setsuko | Masayo Sakai | Shannon Conley | Luci Christian |

| Gosaku | Yoshio Matsuoka | Nick Sullivan | Rob Mungle |

Additional Voices[]

- Original: Masahiro Kanetake (Aunt's house guest), Kiyoshi Yanagawa (Patrolman), Hajime Maki (Man who arrests Seita), Atsuo Omote (Person in bank), Hiroshi Tanaka (Person in bank), Shirō Tamaki (Person in bank), Kiyomi Ajisaka (Person in bank), Teruhisa Harita (Station worker), Michio Denpō (Station worker), Mika Sekita (Nurse), Atsushi Matsumoto (Kid with fishing tackle), Kazuhiko Takeoka (Kid with fishing tackle), Makio Ueno (Kid with fishing tackle), Toyokazu Hiramatsu (Kid with fishing tackle), Takashi Shimatani (Kid with fishing tackle), Ryūji Sanada (Kid with fishing tackle), Tadashi Nakamura, Mariko Miyamoto, Haruko Matsuda, Keiko Ueda, Kyôko Moriwaki, Tamotsu Kuni, Haruo Kaji, Toshiko Ama, Makoto Kobayashi, Ken'ichi Sawada, Ikuo Kokubu, Yūsuke Yokoyama, Yoshinaga Fusamoto, Kōshirō Tanimoto, Masato Moriya, Tetsurō Nakayama, Naoki Fujita, Masafumi Jōno, Tsukasa Ban, Makiko Kinoshita, Senkoku Yukuhara, Yūko Kurokawa, Mayumi Kawaguchi

- 1998 Version: Crispin Freeman (Old Man), Dan Green (Farmer)

- 2012 Version: Andrew Love (Train Station Worker), Justin Doran, Blake Shepard, David Wald

Credits[]

| Credit | Person |

|---|---|

| Director, Screenplay | Isao Takahata |

| Storyboard | Yoshiyuki Momose |

| Character Design, Animation Director | Yoshifumi Kondō |

| Art Director | Nizō Yamamoto |

| Background Art | Eiji Hirakawa, Eiko Sudo, Fukiko Hashizume, Junko Ina, Mutsuo Koseki, Noriko Higuchi, Seiki Tamura, Shūichi Hirata, Toru Hishiyama, Yōji Nakaza, Yoshinari Kinbako |

| Director of Photography | Nobuo Koyama |

| Finish Animation | Akemi Hosotani, Chieko Machida, Etsuko Ohno, Fujino Yonei, Fumiko Saito, Haremi Miyakawa, Harumi Machii, Hideko Sato, Hisako Sagara, Hisako Shitara, Homi Abe, Ikue Nakayama, Junko Igarashi, Junko Yoshikawa, Kazue Hiranuma, Kazue Shiki, Kimie Ishida, Kyooko Ootake, Manami Beppu, Matsuko Horii, Mayumi Watabe, Michiko Nishimaki, Michiyo Iseda, Mieko Asai, Miwako Shibata, Naomi Takahashi, Nobuko Igarashi, Nobuko Nakata, Nobuko Sano, Nobuko Watanabe, Norichika Iwakiri, Reiko Aonuma, Reiko Nanami, Rie Aoki, Rie Yasui, Shinichi Toyonaga, Shizuko Hirai, Taeko Sakuma, Takao Yoshikawa, Takiko Kubota, Tokuko Harada, Toshiko Tawara, Tsutomu Kosuge, Yasuko Yamaguchi, Yoshiko Takasago, Yoshimi Sakuma, Yuki Takagi, Yukiko Matsushita, Yukitaka Shishikai, Yumi Furuya, Yumi Hattori, Yumiko Ichikawa |

| In-Between Animation | Akemi Motohashi, Ako Takano, Atsushi Irie, Aya Satou, Chieko Shiobara, Eiichiro Hirata, Eiichiro Nishiyama, Hideaki Furusawa, Hiromi Kosuda, Hiroshi Inada, Hiroyuki Horiuchi, Hiroyuki Kamura, Hitoshi Kagiyama, Junko Isaka, Kasumi Hara, Keiko Sakuma, Masahiko Ōuchi, Masashi Kaneko, Mayumi Fujimoto, Mayumi Suzuki, Midori Nagaoka, Midori Yamada, Nobuko Sato, Osamu Tanabe, Sachiko Yoneyama, Seiji Handa, Shigehito Tsuji, Shiro Shibata, Sumie Nishido, Takao Maki, Takao Yoshino, Takuya Iinuma, Tatsuji Narita, Tazuko Fukutsuchi, Tokihiko Oota, Tomoko Takei, Tsutomu Awada, Yoko Kida, Yoshie Kawahashi, Yoshimi Kanbara, Yuichi Katayama, Yuko Ogawa, Yumi Kawachi, Yuriko Saito, Yuzumi Enosawa |

| Key Animation | Akio Sakai, Atsuko Otani, Hideaki Anno, Hideo Kawauchi, Hiroshi Ogawa, Iku Ishiguro, Kitarō Kōsaka, Kuniyuki Ishii, Megumi Kagawa, Michiyo Sakurai, Noboru Takano, Noriko Moritomo, Noriko Ōzeki, Reiko Okuyama, Shojuro Yamauchi, Shunji Saida, Toshiyasu Okada, Yasuomi Umetsu, Yoshiji Kigami, Yukiyoshi Hane |

| Sound Director | Yasuo Uragami |

| Production Committee | Kenji Sasaki, Kenjiro Yagi, Kunioki Hatsumi, Shizuya Shibata, Shunichi Satō, Tadahiko Arai, Takanobu Sato, Takashi Nitta, Takuo Murase |

| Music | Michio Mamiya |

| Titles | Hideo Takagu, Toshiko Tagami |

| Editor | Takeshi Seyama |

Live-action version of Grave of Fireflies[]

Nippon TV produced a live-action version of Grave of the Fireflies, in commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II. The movie aired on November 1, 2005. Like the anime, the live-action version of Grave of the Fireflies focuses on two siblings struggling to survive the final days of the war in Kobe, Japan. Unlike the animated version, it tells the story from the point of view of their cousin and deals with the issue of how the war-time environment could change a kind lady to a cold-blooded demon. It stars Japanese celebrity and actress Nanako Matsushima as the aunt. The movie is approximately 2 hours and 28 minutes long.

References[]

- ↑ "Hotaru no Haka". The Big Cartoon DataBase (Retrieved May 13, 2012)

- ↑ "Grave of the Fireflies movie review (1988), Roger Ebert

- ↑ Animage 1987 Interview – Isao Takahata and Akiyuki Nosaka

- ↑ "Akiyuki Nosaka: Author who recalled the fire-bombing of Japanese cities in his best-known work, Grave of the Fireflies", Independent (February 11, 2016)

- ↑ "Grave of the Firefly from My Novel", Asahi Shimbun, Nosaka Akiyuki (Published in the February 27, 1969)

- ↑ "Grave of the Fireflies: Analysis", Buta Connection

- ↑ Akiyuki Nosaka's Lies, Grave of the Firefly, War-damaged Orphan "I am a liar.", Sankei

- ↑ "Grave of the Fireflies: Film Creation", Buta Connection

- ↑ "The Grave of the Fireflies" Lecture at Royal Abbey of Fontevraud, July 2 to 6, 2007

- ↑ "The Animerica Interview: Takahata and Nosaka: Two Grave Voices in Animation", Animerica, Ghibli Blog (1994)

- ↑ The Disney-Tokuma Deal, Nausicaa

- ↑ "GKIDS extends its Studio Ghibli alliance to ‘Grave of the Fireflies’", Uproxx

- ↑ Animerica: Anime & Manga Monthly, June 1993

- ↑ "Central Park Media Files for Chapter 7 Bankruptcy (Update 2)", Anime News Network

- ↑ "Grave of the Fireflies Bluray (2012), Amazon

- ↑ "Kiki's Delivery Service and Grave of the Fireflies Double Play Released Monday", Anime News Network

External Links[]

Official Sites

Information

Encyclopedia

- Grave of the Fireflies on Wikipedia

[]

| |||||||||||||||||||