On MSNBC this morning, I watched Elise Jordan’s focus groups from Green Bay, Wisconsin — the first after the nomination of Kamala Harris. I was honestly shocked that, after the start of this unprecedented presidential campaign by a Black and Asian-American woman, the first voices we’d hear would be from Trump voters. The next group was “right-leaning swing voters.” I was all the more shocked that all the voters in both groups were white. I debated whether to sermonize on this offensive lapse of judgment but instead went light, posting screen grabs of both groups on the socials and asking who might be missing. Enough said, I thought.

Then I got a Twitter DM from Jordan:

This was terribly upsetting. Race-baiting? For pointing out the complete lack of diversity in her focus groups? I responded:

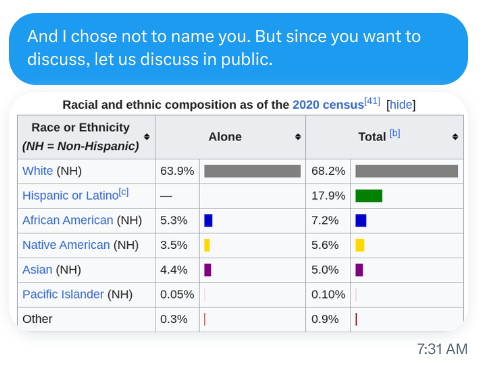

Having been accused of ignorance of Green Bay demographics, I looked them up.

She responded:

I replied:

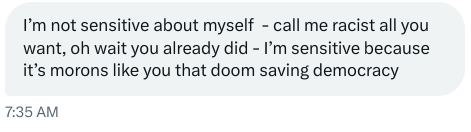

I thought she might back away from the keyboard, but she did not. She escalated.

Morons like me. Dooming democracy. I didn’t want to see this escalate further. I should have replied, “Bless your heart.” Instead I just said:

There it ended. I’ve given this a few hours to settle but I cannot ignore it for a number of reasons.

First, I depend on MSNBC. I’ve lamented that The Times is broken, The Post has been invaded by Murdochians, CNN and NPR are scared and rudderless, Murdoch’s media are victorious with Sinclair on their side, newspapers are mostly in the clutches of hedge funds. We need MSNBC, now more than ever, as the sane network, not afraid of at least speaking with a liberal and diverse public. It is honestly all I watch all day (other than HGTV). But after the MSNBC post-Trump-shooting and Ronna McDaniel debacles, we need to hold to account the executives in charge of the network — executives from a corporation that, as one insider schooled me, “is a Republican company.” My post was my way of saying: I’m watching, MSNBC. Do better.

Second, I have written in my book, The Gutenberg Parenthesis, about the damage to public discourse done by public-opinion polling as well as focus groups, which I’ll quote:

Jordan’s focus groups are all-too-appropriate exhibits for what is wrong with these means of appearing to listen to the body public while instead revealing more about the worldviews of those who pose the questions.

Choosing to lead this first day of focus groups with Trump and “right-leaning” voters showed the judgment of Jordan and her producers. In this unprecedented moment, I’d far rather have heard from some of the 44,000 Black women who gathered on Zoom this week, for they the ones who will decide this election. To lead with white, conservative voters was an explicit choice. It was bad news judgment and a slap to MSNBC’s audience. And there is no transparency into how these individuals were selected.

Jordan’s first question to the Trump voters was whether the nomination of Harris changes the odds of Trump winning. “Everybody’s excited about it and that scares me,” one of the women said. One woman volunteered of the Vice President, “I think she’s an idiot.” To which Jordan asked, “Why do you think she’s not that bright?” And the answer: “Because she hasn’t done anything… she’s not real smart.” Another piped in: “No one respects her.”

None of that is surprising: Trump voters don’t like Kamala Harris. No news there. Wasted airtime. What is surprising is that Jordan only opened the door for further insult.

In what was shown to us, Jordan did not ask them about their own candidate’s intelligence, felonies, sexual predation (this was a group of women), and evident dementia. She did not press them on what they know about the Vice President, only their bad opinions of her.

Next came the so-called swing voters. I am on record doubting that undecided voters are undecided; my theory is that they like attention, such as this. Jordan’s first question to them was to share one concern about Trump and one about Harris — not a positive characteristic of either, but leading with the negative.

“Who do you blame for President Biden’s being in office in this condition?” Jordan asked the group. “Who deserves the blame?” Hang that in the museum of dead journalism, in the collection of leading questions.

One of the participants followed Jordan’s lead, spouting a budding conspiracy theory that, as best as I could interpret it, will end up with Biden leaving office entirely before the election. “If she’s willing to hide that kind of information…. Is is it a power grab or…?” Jordan then asked the group whether this calls into doubt the vice president’s judgment. Objection, your honor. Leading the voters.

To sum up, Jordan and her producers picked two cadres of white, conservatives to give MSNBC viewers their first sense of voters’ worldview in a state and city that Biden won in 2020, if narrowly, and then asked a series of negative and leading questions about the first Black and Asian American women to run for President.

In Jordan’s attack on me in Twitter DMs, she says that it’s morons like me (how’s that for network marketing?) who doom saving democracy. My assumption is that she thinks it is my obligation to hear the ignorant ravings of people known to already hate Biden and Harris or are quick to come to conspiracy theories about them while admitting that they know little about the Vice President.

I believe strongly that journalism must be better at listening to the public it serves. This is why I helped start a degree program in Engagement Journalism and why I am working to expand its reach to more universities. Focus groups and opinion polls are not exercises in proper listening. They are about promulgating the views of the pollsters and about sequestering people into their stereotypes. Indeed, Jordan’s focus groups are, if anything, unfair to the voters they portray by selecting extreme caricatures of Heartland citizens and setting them up for ridicule.

I am empathetic to them for what media does to them — and today’s focus groups are an example. If we are a divided nation, it is media that divides into its demographic and psychographic buckets, red or blue, robbing us of all of nuance and intelligence and reducing public discourse to gotcha bites.

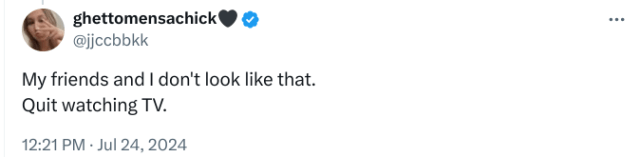

Said one self-reported Trumpist on Twitter in response to the photo of the Trump group above:

Another apparent Trumpist:

An independent:

A lifelong Democrat opined:

And a self-identified centrist independent offered:

At the end of the day, that is the issue: Was this in any way informative? Is public discourse better off for it? Are voters themselves more informed because of it?

Here’s what a journalist I greatly respect said in response to my tweet:

Here’s the video. Is this journalism? Or am I a moron? You decide.