Words by David Peisner | Photos by Michael Stipe & Christy Bush

November 23, 2021

When Michael Stipe was a child, living in a modest house on Medlock Lane, in Decatur, Georgia, he liked to go in the yard and play with roly-polies. These tiny garden creatures, sometimes known as pill bugs or armadillo bugs, are not actually bugs at all, but small crustaceans that feed on decomposed plant matter. They’re best known, though — at least, to anyone who has ever spent time playing in the dirt — for their natural defense mechanism: When touched or frightened, roly-polies curl into a tight ball.

Stipe has led an itinerant life. His father was in the Army, which meant his childhood was a consistent churn of new addresses: Georgia, Texas, Germany, Alabama, Illinois. He and the band he led for more than 30 years are forever associated with Athens, Georgia, and Stipe lived there for a decade or so between the ages of 18 and 27, but even during that time, he was hardly rooted to the place. R.E.M. toured relentlessly during the 1980s, and rarely recorded in Athens, instead decamping to studios in places like North Carolina, London, Indiana, Nashville, Memphis, and Woodstock, New York, to record its first six albums. In more recent years, Stipe has mostly split his time between New York City and Berlin, with regular extended stays in the south of France, where his longtime boyfriend’s family lives, and in Athens, where much of his own family still resides.

“I feel a little like the Gang of Four song, ‘At Home He’s a Tourist,’” Stipe says. “I don’t consider places homes as much as bases.”

It feels significant, then, that last March, when COVID was beginning to shut down the world, Stipe returned to Athens, where he’s kept a house that he bought when he was 25, and where he also maintains an art studio. He wanted to be near his mother, who has had some health issues, but the pandemic lockdown meant living in Athens for the longest block of time he had in many years. He admits that his peripatetic life has left him ill-suited to discern the changes the town and the state have undergone over the last six decades, but there is one he noticed.

“The roly-polies here have changed color since the early 1960s,” he says. “Now they’re turmeric colored, and if you try to move them, it’s almost like when you’re fucking around with lilies and you get the dust from the stamen on your hand. It never washes off.” If Stipe’s entomological observations are accurate — and they very well may not be — roly-polies in Georgia are no longer content to just bunker in defense. They’re going to leave a mark. “It appears that way,” he says, laughing. “They’ve gotten much better.”

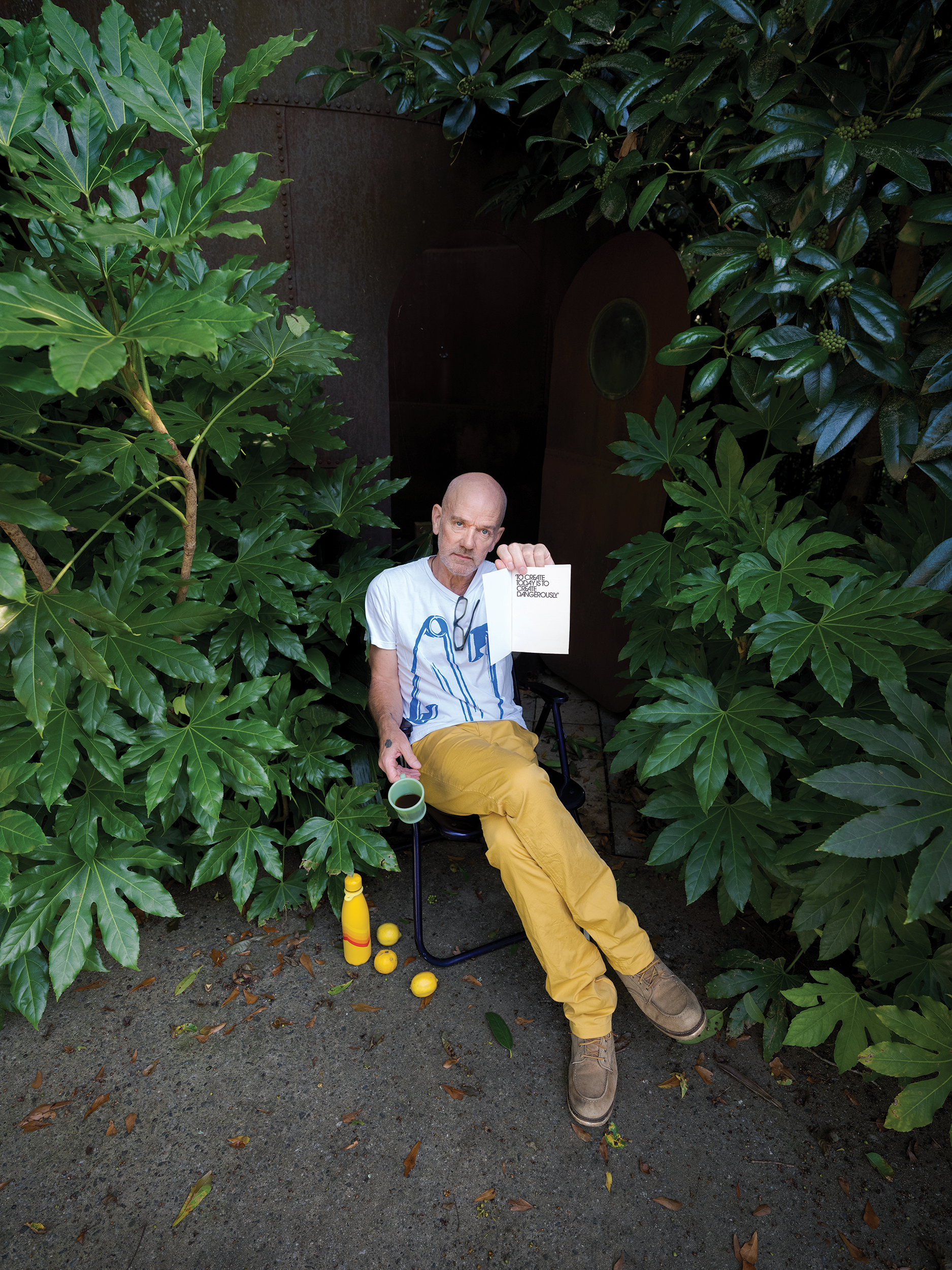

Photo by Christy Bush.

I don’t want to oversell the deeper meaning of the roly-poly anecdote. Sure, it’s cute, but it was just a tossed-off observation at the beginning of a recent, winding conversation I had over Zoom with Stipe, who was sitting in his Athens studio, wearing a white T-shirt designed by an artist friend of his named Dean Sameshima, and black eyeglasses that framed his stubbled face. But it also felt like a tidy way to start thinking about the passage of time. Things change, whether we’re paying attention to them or not, whether we want them to or not. How we deal with those changes is kind of everything.

It’s hard not to think a lot about the passage of time when you’re the 61-year-old former lead singer of one of the most important and admired American rock bands of all time. More than any other group, R.E.M. was responsible for dragging the artsy aesthetic, left-wing politics, and DIY punk ideals of the 1980s indie-rock underground into the pop mainstream. The band sold more than 90 million albums without ever seeming to compromise its musical vision or pander to its fans. Stipe offered a blueprint for a completely different kind of rock ’n’ roll frontman: quietly bold, slyly funny, achingly empathetic, forever thoughtful, and appropriately embarrassed to be a rock star. The band’s measured rise to superstardom became the platonic ideal for a generation of artists that followed, and their influence shaped not only the sound of the alternative-rock revolution of the 1990s but also its moral compass. Then, after a series of albums in the late ’90s and 2000s that received a more muted public reception but which, in many cases, have aged better than the band’s multi-platinum-selling classics, R.E.M. did the strangest of all things and amicably called it quits in 2011.

Since then, Stipe has been steadfast in waving off any hint of a return for the band, and unlike many other artists of his vintage whose reunion denials always seem to imply a nod, a wink, and the hope of a large check from Coachella or Lollapalooza, you get the feeling the former R.E.M. singer is dead fucking serious. What’s done is done.

“I’m very proud of what we did as a band, and I’m very proud of my contributions to our successes and our failures,” he says, as he runs his hands back and forth a few times over his bald head.

His voice has the same warm, quietly authoritative timbre recognizable from three decades of R.E.M. songs, but in conversation, the words tumble out with a slightly frantic edge. “Every single thing that we put out through the band, we thought at the time was the absolute best thing that we could do,” he continues. “I embrace it all. But it was all-encompassing, and it was exhausting. I was really tired after 32 years. It was a lot.” As he put it rather definitively in an interview a couple of years ago, “Everything has a life, and at some point, it ends.” So yeah, the passage of time.

“I’m trying desperately to be in the present, and to allow for the presence of the present,” Stipe says, and then laughs. “I’m sorry. That sounds so stupid, but I tend to focus on the past and the future, so I’m trying to be more in the moment.”

T-shirt by Vote.org. Questions based on “Three Things to Ask Yourself” from Stacey Abrams. Clipboard from Mr. Ginn, father of Greg Ginn and Raymond Pettibon. Vintage ’70s vote tie from Vote for Change 2004 tour. Self-portrait by Michael Stipe.

In the years following the band’s dissolution, Stipe stepped away from music completely, instead focusing on his work as a visual artist, specifically (though not exclusively) photography and sculpture. He’d been taking photographs consistently since he was 14, and majored in studio art at the University of Georgia before dropping out to devote his time to R.E.M. “It’s so nice to make something that’s tangible, that I can hold in my hand,” he says. “Because most of my life as a creative person, I was making things — through music or voice or lyrics — that you can’t touch.” In his Athens studio, he’s surrounded by a lot of these tangible things, the sculptures, photos, books, and other ephemera that have been both the inspiration for and the product of his recent artistic ventures. “I’m not going to do a show-and-tell,” he tells me, but shortly after proceeds to do exactly that.

He starts with photos he took back in 2007 for a project called Future Epicenter. “That’s a close-up of a pornographic image of a guy’s foot,” he says, flashing a page from a photo collection up to the Zoom lens. “This is a close-up of my computer screen. You can see all the fingerprints on the screen.” The point of the project, he tells me, was to post a digital photo every day for a year. “The idea was that after 365 days of doing this, I’d be able to look back and acknowledge how I looked at the world before digital cameras and how I’m looking at the world now, through digital cameras. And it was this profoundly, radically different vision.”

Around the same time, Stipe had his first sculpture installation at the opening of an upscale men’s clothing store in Manhattan. For it, he cast recent cultural artifacts — including Polaroid cameras, cassette tapes, and clock radios — in bronze. One of the people who saw that exhibit was Ruth Lingen, an artist who specializes in printing, papermaking, and bookbinding. A few years later, she began working with Stipe on a very limited-edition photo book (only seven were made) called Giants of the 20th Century. “It was sort of the same idea in print form,” she says. The book collected photographs of what Lingen describes as “future relic kind of things,” including the Concorde, the Dewey Decimal System, the United Nations, and Marlon Brando. Some of it was Stipe’s own photography, but some was “re-photographing photographs that he had. It was interesting because it was a re-conceptualizing of these everyday objects.”

Stipe says: “Giants of the 20th Century detailed very important aspects of the 20th century that didn’t quite make it into the 21st century. And the truth is, they actually all did, but they didn’t in the way we thought that they would. They entered it differently.” The same, of course, could be said of Stipe himself.

How the past makes its way, often inelegantly, into the present has been a thread running through a lot of Stipe’s work, going back at least to R.E.M.’s canonical “It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine),” a breathless, dizzying recitation of historical images that anticipates the annihilating, context-free blur of a social media scroll better than anything else in 1987 could have. That thread was tweezed apart when Stipe worked with his friend, Generation X author and noted futurist Douglas Coupland, on a photo book called Our Interference Times: A Visual Record, which pondered the messy intersection between the analog and digital worlds. The photos in the book reveled in the misuse of digital technology: an iPhone photo of a laptop screen displaying an image originally taken with a film camera; a photo of a window that had been Xeroxed over and over until it could no longer be identified as a window. The effect is disorienting, chaotic, and not entirely dissimilar from “It’s the End of the World as We Know It.”

“The common thread is me and my eye, and often my life,” Stipe says. He takes photos constantly and has done so for many years. So, in one way or another, even if he’s taking photos of someone else’s photos, the perspective is always his, and the experience he’s chronicling, in toto, is, if not quite autobiographical, certainly his own. “There is an aspect of it that is a part of me and that shows, in some regard, how I look at the world and how I move through it.” Which is to say, with an awareness that the past — to quote another Southern wordsmith — is never dead. It’s not even past.

Wearing a Bootleg Fassbinder Fox and His Friends T-shirt by Dean Sameshima. Self-portrait by Michael Stipe.

On February 26, 2020, Stipe went to a Tibet House US benefit concert at Carnegie Hall featuring, among others, Patti Smith, Bettye LaVette, Phoebe Bridgers, and Laurie Anderson. Stipe was with Caroline Wallner, one of his closest friends, and Wallner’s three daughters, the eldest of whom is Stipe’s goddaughter. At the time, COVID was not much more than a rumor, a potentially dispiriting bit of international news floating in the ether. There were troubling reports coming out of China. There were epidemiologists offering anxious warnings on NPR. But most of us were still happily cocooned in our ignorance, assuming that COVID would go the way of SARS, MERS, and swine flu before it: Frightening public health emergencies that were mostly only emergencies for other people.

Stipe was more worried than most, though. That night, Wallner recalls him toting along disinfectant spray, which he used to disinfect their seats on the subway and the pepper shaker at the restaurant they went to before the show. Following the concert, there was an after-party. People talked. They embraced. “It’s pretty scary now when you think about it,” says Wallner. “Hal Willner was there and we hugged him.” Willner, an iconoclastic producer who worked on albums by Lou Reed, Marianne Faithfull, and Allen Ginsberg, was a good friend of Stipe’s. He died almost six weeks later of COVID. “That particular show was the last concert either of us went to,” says Wallner.

By mid-March, Stipe was locked down in Athens. He had been previously leading a very social life, so the sudden isolation was unsettling. “I’m weirdly extroverted,” he says. “I like being out every night. It takes me out of my head and provides me with a way to stop thinking, and just listen and observe — all the things that go into the work I do as an artist, whatever medium I’m working in.” Although he was going a little stir crazy, he made an important discovery. “I’m OK with my own company. There were months and months when I was, in essence, alone. I’m OK with that.”

Stipe brings up a statistic he stumbled upon sometime in the early ’90s in Harper’s Index, a recurring feature in the long-running monthly magazine. “There’s more information contained in a weekday edition of The New York Times than the average person living in the 1800s was likely to encounter in a lifetime,” he says, quoting it from memory, seemingly not for the first time. That fact got him thinking recently about the value — or lack thereof — of information. “Information,” he says, “can create schisms. I think that’s the accurate term, because it feels weirdly faith-based.” Forget the weekday edition of The New York Times; with the internet, people today are drowning in information. “The truth is we now know everything. But as Douglas Coupland says, ‘Knowing everything actually isn’t that illuminating.’ Knowing everything means we question what is reality, what is truth. That’s where we find ourselves now. We’re in the middle of a pandemic and people are questioning very basic truths about science and medicine.”

Speaking about his upcoming, untitled book, Stipe says, “It’s a little bit of a diary of people who got me through a very difficult time.”

The arguments on our TVs, on social media, and at our dinner tables have often felt less like a debate over masks or vaccines or politics and more like a rejection of the last 400 years of human progress, a stark reconsideration of the Age of Enlightenment. Although it’s too soon to see how it will all shake out in the long term, it’s clear something foundational is slipping underfoot. “I think of last year as a pivotal shift from one epoch to another,” says Stipe. “Now, there will always be before and after COVID.”

Stipe had already begun working on a new photography book before the pandemic began, back in 2019. His original plan was to travel to take portraits of people whose courage, strength, and vulnerability he admired, but he’d taken only a few — of actress Tilda Swinton and poet John Giorno, among others — before COVID scuttled those plans. Instead, the resulting project is a hybrid: There are the portraits he’d already taken, there are photos from his archive, and then there are, well, names. Lots of them. Some of the names are painted onto vases sculpted by Wallner, who is a ceramicist. Some are printed onto book covers designed by Lingen, or spelled out in assorted fonts.

“Because I couldn’t travel to see anyone, the idea expanded to become people who were, for one reason or another, heroic to me or had impacted me during that year of lockdown,” says Stipe. “It’s a little bit of a diary of people who got me through a very difficult time.”

Stipe chose vases and book covers because both were “vessels that contained things,” but it’s the relentless profusion of names that is maybe the most interesting and puzzling part of the book. As he leafs through the pages and shows them to me, there are the famous (LeBron James, Cher, Thom Yorke, Stacey Abrams), the semi-famous (Alek Wek, Tom Gilroy, Sally Mann), and the not-really-famous-at-all (Jay Maloney, Sue Wildish, Patrick So). The way the names are rendered is supposed to elucidate some part of their character, though that’s tricky to pin down.

Lingen says that seeing the final book after having worked on only a part of it was a revelation. “There’s this thing that happened during COVID which was like a weird Groundhog Day of repetition, over and over,” she says. “So the names, the people’s faces coming at you, the feeling of isolation, of longing, I think he really pulled all that together. There’s a melancholy to this book.”

Stipe’s pandemic trauma hasn’t necessarily been any worse than yours or anyone else’s — in fact, as he admits, his wealth and status give him advantages most others don’t have — but that doesn’t make it less valid. In fact, that his trauma is fundamentally the same as yours is perhaps strangely reassuring, if not unifying. COVID will one day be a ghost story you tell your grandkids (fingers crossed!), but the existential questions it has raised won’t disappear with it. How do we live through a moment when all the days blur together and time seems to stand still, yet the mounting death toll drills home just how fleeting life is? When only the past and the future seem worth considering, what the fuck do we do with today?

“How to Work Better” by Peter Fischli and David Weiss. Bootleg Fassbinder Querelle T-shirt by Dean Sameshima. Self-portrait by Michael Stipe.

“I’m trying desperately to be in the present, and to allow for the presence of the present,” Stipe says, and then laughs. “I’m sorry. That sounds so stupid, but I tend to focus on the past and the future, so I’m trying to be more in the moment. This book was a way of allowing me to be present in a very difficult period.”

The book was published in April and is officially untitled. For some reason, Amazon lists it with the title Portraits Still Life, which on one level feels like a hilariously dry, generic moniker that might have been spat out by an algorithm, but which on an entirely different level takes on many shades of meaning depending on which words you choose to emphasize. I like to think of “still life” referring to our stagnant existences in lockdown, or maybe that these portraits, collected during this stultifying time, are nonetheless still life. As if to say, this is the present whether you like it or not.

Wallner suggests that the book could be seen simply as “a directory of really cool people to look up,” which also fits pretty well with Stipe’s general manner of engaging with the world. Taking photos has long been a way of focusing attention away from himself and onto other people. “He has this beautiful way of being humble around everything,” says Wallner, who first met Stipe when both were art students at UGA. “He’d be the guy at the party perched on a beam with his camera, taking pictures. He’d always be like, ‘Oh, my God, stand still right there, just the way the light falls on you.’ That’s his way of communicating.”

When Stipe was the lead singer of one of the biggest bands in the world, the very act of putting himself at the other end of a camera automatically changed the power dynamics in the room. It put people at ease. And the direction he chooses to point his camera can be just as authorial as his lyric writing. As such, his life’s work is not just music or photography or sculpture, but also curation. Whether he’s pointing your attention toward Andy Kaufman, Howard Finster, Lenny Bruce, John Giorno, or Greta Thunberg, Stipe is constantly evangelizing about the work of others. “Michael, to me, he’s a celebratorian,” says Wallner. “He celebrates people.”

My conversation with him includes dozens of references to people whose work and/or lives he admires, including Steve McQueen, John Baldessari, Destroy All Monsters, John Lewis, Dewayne “Lee” Johnson, Kofi Annan, and Jenny Holzer. At one point, he asks about a piece of artwork over my right shoulder that he likes. The artist in question, I tell him, is my daughter. She painted it when she was about 8.

“I like what she did with the corners,” he says evenly. “It reminds me of R.A. Miller. He’s an outsider artist from outside Gainesville, Georgia, who I was friends with way back in the day. You should look him up. I think you’ll like his work. He’s now deceased. Also, there’s another Georgia artist named Billy Lemming. He’s also gone now.”

A lot of the people Stipe mentions to me are dead, as are many of those named or photographed in the new book, which is perhaps sadly appropriate for any project that chronicles a year as death-haunted as this past one has been. Lingen says she and Stipe even had a nickname for the white book covers she designed to represent dead heroes, including Michael Hutchence, Edward Albee, and June Carter Cash. “We called them the ghosts,” she says.

Look, it’s a reasonable first impulse to dismiss a famous rock star’s late-career turn toward becoming a serious artist with a deep groan. It is, in fact, probably wise to view such a transition with extreme skepticism. The thing is, though, Michael Stipe has always been a serious artist. The fact that even after dropping out of UGA, he remained a lifelong student of visual and conceptual art, a lifelong collector of it, is less convincing to me than the fact that his music has always felt like art. It has always been about something, even — and maybe, especially — when it wasn’t at all clear what that something was. I don’t know what “Radio Free Europe,” “Drive,” “Fall on Me,” or “E-Bow the Letter” are about — and, frankly, I’m not so sure Stipe does either — but every time I hear them, they make me want to figure it out.

It’s no different with his artwork. I mean, the first time I looked through the pages of this new book and saw lists of names in odd fonts, pictures of vases and book covers, and some photographs of photographs that Stipe didn’t even take himself, I thought, “What the fuck is this?” But I kept looking. I kept wanting to know. It made me feel something. And even now that he and the people he worked on it with have explained it to me, I’m still not sure what it all means. Or at least what it means to me. And that’s something.

Michael Stipe, Madrid, Spain, 1999. Photo by Christy Bush.

Late one night, in the early 1990s, Stipe was in Athens, hanging out with Todd McBride, who was then the lead singer of a great bar band called the Dashboard Saviors, and the wonderfully eccentric singer-songwriter Vic Chesnutt. The three were at The Grit, a cheap, vegetarian restaurant that has become one of the college town’s more iconic downtown eateries but which at the time was in a different building, closer to the edge of town. As McBride explained when he told me this story more than a decade ago, “The Grit was in this depot kind of building then — it was down at one end and this frat bar was down at the other. The place was closing up, we were getting ready to leave, and we were kind of hanging around outside The Grit, when this jeep full of frat boys comes by, throws a beer can at us, and screams, ‘Fuck you, faggots!’ Then they crank up the stereo” — at this point in his telling of the story, McBride began to sing the indelible song that was pumping from the jeep’s stereo — “It’s the end of the world as we know it / It’s the end of the ...”

So there are Stipe, Chesnutt, and McBride, three giants of the Athens music scene, silent and a little befuddled outside The Grit. “We all kind of look at each other,” McBride recalled, “and Michael goes, ‘You know, people say you can’t really define irony ...’” And with this, McBride collapsed into peals of laughter.

I’ve always liked that story because although it seems like it’s about Stipe — who said he doesn’t remember that exact night but is “sure it happened” — and his bone-dry sense of humor, it’s maybe more about Athens, and all the places like it, not just in the South, but all over the country. It’s also a story about both the power and the limits of art. You can charm your way onto somebody’s stereo, onto their coffee table, or even into their head, but changing their perspective is much, much harder.

Chesnutt once told me that he wrote songs for his “betters” — people who were smarter than him, more well-read, more creative. “I feel like 99% of people are not gonna get most of my songs,” he said. He was right. Stipe arguably writes for his betters, too, but during his time with R.E.M., the 99% got them. Or even if they didn’t get them, they heard them, they liked them, and they were more than happy to blast them from a jeep on a Friday night in Athens. Peter Buck, Mike Mills, and Bill Berry deserve a certain amount of credit — or blame — for this, but it’s Stipe’s singing — tender, resolute, and often otherworldly — that has always felt like an open invitation.

“The voice is the voice,” he says. “I admire it and still almost can’t believe that it comes out of me. I do feel like I’ve been able to offer things to that voice that are important to individuals’ lives or helped someone out of a bad mood one day, or helped put them in a bad mood to realize that they’re not alone in their sadness about this or that thing, whether it’s unrequited love or politics or just some existential fucking crisis that we’re apparently going through on a daily basis now.”

Whatever the reason, that 99% — not all of them riding in jeeps, hurling beer cans and homophobic slurs — has expectations. They always have. Mainly, they want their favorite band to keep being their favorite band, exactly as it always has been. They want the past to be the present and the future. Of course, that can never be, though it has not stopped much of the world from trying to make it so.

Which is a roundabout way of acknowledging that Stipe is making music again. He claims that it happened “quite by accident,” though this isn’t exactly true. In 2017, he collaborated with another Athens musician, Andy LeMaster, on music to accompany an audio-video art installation at Moogfest in Durham, North Carolina. The installation, called “Jeremy Dance,” was — as befits the vision of a lifelong curator, always grappling with the past — a tribute to his then-recently-deceased friend, the Athens artist and poet Jeremy Ayers. The following year, Stipe teamed up again with LeMaster on a similar project, “Thibault Dance,” which featured French dancer Thibault Lac. Around the same time, he and LeMaster wrote and produced for an album by the electro-rock duo Fischerspooner. Somewhat unexpectedly, Stipe found himself with old itches he wanted to scratch. “I stepped away from it for years, and then I really wanted to sing again,” he says. “I like singing.”

The next fruit of this burst of creativity, a dark, throbbing pop song called “Your Capricious Soul,” appeared in 2019, and began a slow drip of solo singles. The song that followed, the moody, hypnotic “Drive to the Ocean,” was cut from the same sonic cloth. Both were collaborations with LeMaster, who previously led the band Now It’s Overhead and is a co-owner of the iconic Athens studio Chase Park Transduction.

“Michael always wants to do something new,” says LeMaster. “He doesn’t want to do the same thing again. No matter who you are, if the majority of your writing has been collaborative with the same group of people and then suddenly you’re on your own, that’s a pretty exciting whole new way to look at things.”

Stipe in his Athens studio with an image from his parents’ honeymoon in 1956. This will be part of his upcoming ICA Milano exhibition next year. Self-portrait by Michael Stipe.

For the first time in his career, Stipe is writing music along with the lyrics — “My god, it’s so hard,” he laughs — but he cedes a lot of the technical work. “If I’m able to handle the engineering stuff, it really allows him to see the forest for the trees,” says LeMaster. “He’s so good at keeping the big picture in mind.”

Stipe’s most recent single, “No Time for Love Like Now,” which appeared last June, feels of a piece with the other two but is a collaboration with Big Red Machine, the side project of The National’s Aaron Dessner, along with Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon. The song was written before the pandemic, but feels prescient about the lockdown that was on the horizon, and is animated by Stipe’s struggle to live in the present. “Whatever waiting means in this new place,” he sings achingly, “I am waiting for you.” It’s still life.

None of the new music sounds particularly like R.E.M., but because Stipe is such a singular vocalist, it feels a little like his former band. He may not want to live in the past, but the past lives in him whether he likes it or not. Stipe has other songs he’s recorded with LeMaster in various states of completion, but no real strategic plan for how they’ll eventually be released. “I have no record company, I have no contract, I don’t have any representation,” he says. “I’m happy to put out my stuff and not feel like I have to compete with a Dua Lipa or Miley Cyrus or whoever is at the top of the charts this week.”

Which is not to say he is without ambition for the future. Music is not a lark to him — it’s never been — just don’t expect it to dominate his life as it once did. Next year, he’ll have a solo sculptural exhibit at the Fondazione ICA Milano, and as he casts his eyes further down the road, he can imagine a professional future that feels more balanced than his past. “I hope that I have an entire bookshelf with all kinds of books I’ve created,” he says. “I hope I have a whole body of new music, post-R.E.M., to contrast and amplify the great work I did with R.E.M.”

The future, it seems, is always made up of bits of the past. I ask him about a striking black and white photograph of a young couple that sits behind him in his studio. “It’s a piece I made for a series I was doing of images from my past,” he says, motioning to the photo. “This is pre-me. This is my mother and father on the day that they were married and went off on their honeymoon.” Stipe’s father died six years ago, but his mother, he tells me, is actually on her way over as we speak.

As for the present that Stipe is trying hard to allow for the presence of, it’s as straightforward as it’s ever been. “I just work every day,” he says. “I’m making things all the time.” He looks around at the artwork, papers, and photos stacked, piled, and scattered around his studio — remnants of the past, fuel for the future — then shrugs a little. “That’s where I find myself at the grand old age of 61: pretty happy.”

David Peisner is a journalist based in Decatur, Georgia. He is a contributor to The New York Times, Rolling Stone, and New York magazine, as well as the author of Homey Don't Play That!: The Story of In Living Color and the Black Comedy Revolution, which was published in 2018 by 37 Ink/Simon & Schuster.

Christy Bush is a fine art and fashion photographer living in Athens, Georgia. She is known for her whimsical, intimate, and joyful approach to her subjects. Her work has been shown in New York, Paris, Japan, and Atlanta. Recent publications include Fat Magazine (Denmark), Lovewant (Australia), and Index (New Zealand).